An Oldie Outdoors

About

No tough guy and no expert, just an ordinary oldie who likes the outdoors and randonnees pedestres.

Perversely, considering I hate heights and the cold, I’m fond of blundering up hills. Intermittently I leave unhilly Norfolk on unambitious adventures. Blogging about them, I reflect on my inability to choose reliable gear and muse on outdoor life. Nothing extreme or life-threatening. A slight emphasis on food.

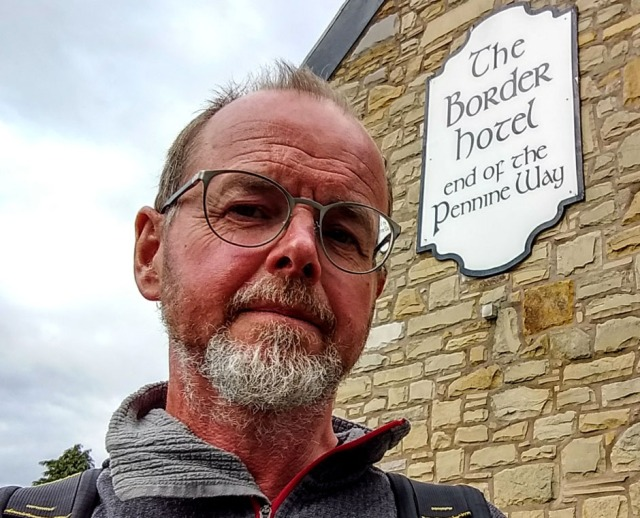

Among other things, my blog documents three of my four completions of the Pennine Way, England’s oldest and best National Trail, and my adventures on the Scottish National Trail and the Hebridean Way. I’m grateful for any comments; thanks for your visit and best wishes, Andrew.

Sunrise over Blackton Reservoir from Clove Lodge, Pennine Way.

Trail Blog

Pennine Way Blog – South to North

Welcome to The Pleasant Pennine Way blog. The Perverse Pennine Way blog is also available. Either Way, I hope you’ll find these blogs useful if you’re planning a challenging but enjoyable walk along England’s oldest and best National Trail.

Click here to jump to the ‘pleasant’ itinerary, a conventional south to north nineteen day walk in late May and early June 2016. That’s pretty much the optimum time of year, although a week later would have been even better for wild flowers. This walk took in most of the standard stops and, although it had its moments, was ultimately achievable even for an oldie of moderate fitness. I based the plan on my first Pennine Way, walked back in April 1999 when I was young and blithe.

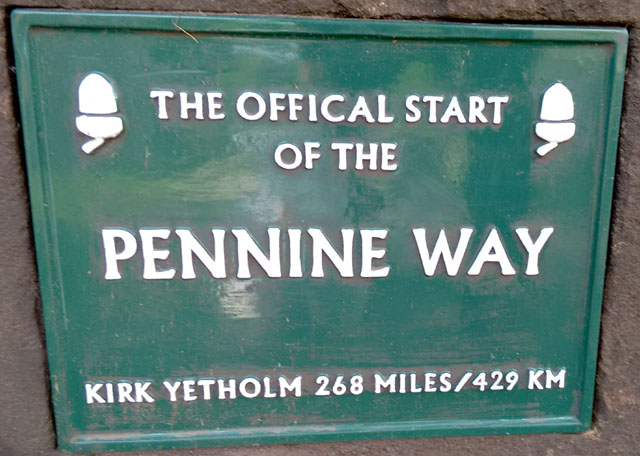

The Pennine Way, offically created before the miracle of autocorrect.

Despite longer, drier summer days, better gear and better knowledge (ha ha), I was more cautious this time, allowing nineteen days instead of 1999’s seventeen. I was older, I’d been troubled by foot and knee pain and between Gargrave and Steel Rigg I was to be accompanied. The latter was an excuse to book a few accommodations more luxurious than I’d have justified walking alone.

Complications of companionship also decreed ambitiously compressing the standard first five days into four. I wouldn’t recommend this for a first Pennine Way; many people fall by the Wayside within those early days as it is. Unless you’re already hill-fit, I’d start more slowly and speed up. I could barely speak on staggering into Gargrave.

When I did struggle (on days three, four and 18), this was caused by hurrying to reach particular places. Given the ample daylight and benign weather, I could have knocked a day or two off the walk overall by taking greater advantage of my tent to distribute the miles more evenly. I’d also suggest at least one complete, pack-off, rest day rather than a couple of short walking days, which don’t seem to have the same restorative effect. I’m assuming a tent. To me, a Pennine Way without camping is like the proverbially unpedalled pisciforme.

Many Pennine Way blogs are litanies of pain and misadventure, but this was a wonderful walk. I enjoyed it so much I did it again four months later. We didn’t get lost to any really troubling extent, but then I’d done the trail before. We didn’t fall into life-threatening bogs or freeze or have to be rescued, but then it was June. The days were light, dry-ish, cool and wonderfully long.

On the downside, the latter tempts you to do too much, hostels have to be booked and it’s virtually impossible to sleep on campsites noisy with families.

Guidebook references with page numbers are to Pennine Way – Official National Trail Guide by Damian Hall, Aurum Press (‘NTG’), although this walk was actually done using collapsible vintage copies of the previous two-volume NTG by Tony Hopkins*. References to Wainwright are to his Pennine Way Companion. Simon Armitage references are to Walking Home – Travels with a Troubadour on the Pennine Way, Faber, 2012. Grid references are OSGB, estimated by eye from the NTG maps or in some cases noted while on The Way from the free smartphone app OS Locate. In all cases they’re approximate and subject to error, as are any bearings.

Don’t rely on this blog for ‘live’ navigation on The Way. Things change, I make mistakes, I’m no expert. This blog is for entertainment, it describes the Pennine Way as it was in June 2016 and won’t be updated. This trail involves rough hillwalking often in challenging weather. Even for the suitably experienced and equipped, it can be hazardous.

*I’ve since been converted to the A to Z guides which are light and ideal – just the OS maps bound together with no extra weight of pointless persiflage.

Here’s the bare bones itinerary, with links to the blogs. Distances and elevations are estimated on Google Mapometer, rounded them to the nearest 1 km, 1 mile, 10 m and 10 feet. Hence they don’t convert consistently, like recipes. They’re just a rough indication for basic planning.

edale pennine way peak district derbyshire england tent campsite

Upper Booth

Pre-day: May 27th

Travel by train to Edale, arrive late afternoon.

Camped at Upper Booth farm campsite (booking essential).

Day 1: May 28th

bleaklow cairn peak district derbyshire pennine way hiking trekking hillwalking

Bleaklow

25 km, + 680 m, – 750 m. 16 miles, + 2240 ft, – 2460 ft.

Upper Booth to Crowden via Kinder Downfall and Bleaklow. Camped at Crowden campsite.

Day 2: May 29th

laddow rocks peak district derbyshire pennine way hike hillwalking wild camp rock climbing

Laddow Rocks

33 km, + 910 m, – 750 m. 21 miles, + 2980 ft, – 2460 ft.

Crowden to Light Hazzles Edge, via Black Hill and The White House Inn.

Wild camped at Light Hazzles.

Day 3: May 30th.

hebden bridge pennine way yorkshire moorland hike trek

King Common

29 km, + 670 m, – 830 m, 17 miles, + 2180 ft, – 2710 ft.

Light Hazzles to Ponden, via Stoodley Pike, May’s Shop and Top Withins.

Camped at Ponden Mill campsite.

Day 4: May 31st

yorkshire pennine way moorland hiking trekking trail long distance england

Ickornshaw Moor

28 km, + 730 m, – 840 m. 17 miles, + 2410 ft, – 2760 ft.

Ponden to Gargrave, via The Hare and Hounds at Lothersdale.

Bed and Beakfast at The Masons’ Arms, Gargrave (pre-booked).

Day 5: June 1st

yorkshire dales camping campsite pennine way england limestone karst tent

Malham Beck

11 km, + 210 m, – 120 m. 7 miles, + 680 ft, – 390 ft.

Gargrave to Malham, an easy recovery day.

Camped at Town Head Farm campsite on Malham Beck.

Day 6: June 2nd

limestone karst landscape yorkshire dales pennine way england

Malham

24 km, + 830 m, – 800 m. 15 miles, + 2710 ft, – 2610 ft.

Malham to Horton in Ribblesdale via Fountains Fell and Penyghent.

Bunkhouse at The Golden Lion (pre-booked).

Day 7: June 3rd

yorkshire dales horton ribblesdale pennine way england trail long distance walk

Cam High Road

22 km, + 450 m, – 450 m. 14 miles, +1480 ft, -1480 ft.

Horton to Hawes via the Cam High Road.

Bed and Breakfast at The Old Board Inn (pre-booked).

Day 8: June 4th

yorkshire wensleydales hawes pennine way england summit long distance trail

Great Shunner Fell

20 km, + 710 m, – 620 m. 13 miles, + 2320 ft, – 2050 ft.

Hawes to Keld, via Great Shunner Fell and Thwaite.

Camped at Swaledale Yurts (pre-booked).

Day 9: June 5th

yorkshire highest pub england dales bikers hiking real ale

Tan Hill

June 5th. Keld to Tan Hill.

7 km, + 280 m, – 80m. 4 miles, + 930 ft, – 270 ft.

Camped at Tan Hill Inn (no booking). Another easy recovery day.

Day 10: June 6th

county durham limestone karst england pennine way walkers hikers

God’s Bridge

16 km, +200 m, – 400 m. 10 miles, + 650 ft, – 1310 ft.

Tan Hill to Clove Lodge, via Sleightholme Moor and God’s Bridge.

Bunk Barn at Clove Lodge (pre-booked, check availability).

Day 11: June 7th

baldersdale-pennine-way-sunrise-blackton

Baldersdale

25 km, + 540 m, – 470 m. 16 miles, + 1750 ft, – 1550 ft.

Clove Lodge to Langdon Beck, via Middleton in Teesdale.

Hostel at Langdon Beck (YHA, pre-booked).

Day 12: June 8th

teesdale county durham england waterfall cow green pennine way

Cauldron Snout

20 km, + 380 m, – 580 m. 13 miles, + 1230 ft, – 1900 ft.

Langdon Beck to Dufton via Cauldron Snout and High Cup.

Hostel at Dufton (YHA, pre-booked).

Day 13: June 9th

cumbria summit pennines highest point pennine way cairn trig

Cross Fell

25 km, + 940 m, – 770 m. 15 miles, + 3080 ft, – 2520 ft.

Dufton to Garrigill, via Cross Fell.

Camped at Garrigill Village Hall (normally no need to book).

Day 14: June 10th

northumberland pennine way england burn long distance walk national trail

Gilderdale

20 km, + 260 m, – 400 m. 12 miles, + 850 ft, – 1300 ft.

Garrigill to Knarsdale, via Alston.

Camped at Stone Hall Farm campsite, Knarsdale (normally no need to book).

Day 15: June 11th

northumberland england pennine way roman fort picts border national trail

Hadrian’s Wall

28 km, + 620m, – 610 m.17 miles, + 2040 ft, – 2000 ft.

Knarsdale to Once Brewed, via Greenhead and Hadrian’s Wall.

Bed and Breakfast at Vallum Lodge (pre-booked).

Day 16: June 12th

northumberland kielder pennine way national trail england hike walk

Wark Forest

25 km, + 430 m, – 530 m. 15 miles, + 1420 ft, – 1750 ft.

Once Brewed to Bellingham, via Rapishaw Gap, Wark Forest and Horneystead.

Bunk Barn at Demesne Farm (pre-booked).

Day 17: June 13th

pennine way northumberland england long distance national trail moorland peat

Whitley Pike

25 km, + 580 m, – 470 m. 15 miles, + 1890 ft, – 1540 ft.

Bellingham to Byrness, via Whitley Pike and Redesdale Forest.

Bunkhouse at the Forest View Inn, Byrness (pre-booked).

Day 18: June 14th

northumberland kielder pennine way cheviot forest view byrness hillwalking trekking

Redesdale

33 km, + 1160 m, – 790 m. 20 miles, + 3800 ft, – 2600 ft.

Byrness to The Schil, via Windy Gyle and Auchope Cairn.

Wild camped on The Schil.

Day 19: June 15th

pennine way schil scotland borders cheviot camping hiking hillwalking coleman aravis tent trek trekking

The Schil

9 km, + 180 m, – 650 m. 5 miles, + 600 ft, – 2130 ft.

The Schil to Kirk Yetholm (high option).

Hostel at Kirk Yetholm (Friends of Nature, pre-booked).

Post-day: June 16th

river tweed england scotland border railway bridge

Berwick

Buses from Kirk Yetholm to Berwick on Tweed, via Kelso.

Hostel at Berwick (YHA, pre-booked). Train home on the 17th.

General Pennine Way Tips

As well as time of year, type of accommodation and a rough schedule, one of the most important decisions is choice of footwear. Our number one problem was sore feet. I was pretty much unblistered as my boots were worn in and I was proactive and pre-emptive with the Compeed. I ‘merely’ suffered unpleasant toe and metatarsal pain on descents, inexplicable instep bruising (only on my left foot) and eventually unattractive, itchy foot rot. My companion unfortunately did encounter the Wayfarers’ number one curse of blisters and, like so many, was unable to complete her planned walk because of them. We both wore mid-weight, upper-mid-price leather boots.

That decision was based on my 1999 experience walking The Way in suede, fabric and Goretex hybrid boots, Karrimor KSBs. I still recall those boots with loathing. They were comfortable, but they leaked like sieves from around day eight. Barely-thawed bog water constantly trickled into them, even with gaiters, Nikwax was no help and from Hawes northwards my feet were permanently soaked and freezing (I also acquired frostbitten ears – The Way in April can be quite hardcore if you’ve no idea what you’re doing). I thought leather boots would be better, but in fact this time my Goretex lined Scarpa Rangers behaved identically! From around day eight they too leaked, rendering their weight and bulk pointless.

After completing this Pennine Way I subsequently walked the entire trail a third time, in October 2016. I walked it nimbly and lightly, with no foot pain, rot or blisters. How? By finally heeding advice I’d heard often from wiser walkers. Ditch the heavy, soggy boots and walk in trail shoes. For three season fellwalking in the largely unpointy Pennines, for me personally it’s now that simple.

Guess what: my Goretex lined trail shoes leaked too, and from around day eight! It seems no Goretex footwear can remain waterproof for more than a week or so on the Pennine Way. But, being light and minimally structured, they dried quickly too.

One more thing on footwear – I routinely ditch all insoles, however fancy, and replace them with Sorbothane Double Strikes. In my opinion the three essentials of long distance walking are Sorbothane insoles, Compeed and trekking poles. These are all to do with saving your feet and knees, which will then drag the rest of you with them, along – The Pleasant Pennine Way…

PENNINE WAY BLOG 3 – DAYS 1 – 3.

The Purposeless Pennine Way, in which I set out purposefully and happily to complete my favourite trail, while disclaiming purpose and anticipating pain.

You may have seen the BBC programmes ‘celebrating’ the fiftieth anniversary of the Pennine Way. To me they were a travesty. An opportunity for some immortal ‘slow TV’ squandered in favour of a catalogue of breathless ‘adventures’. Most of these were nothing to do with walking the trail and communicated nothing authentic about the experience of doing so. Just more box ticking, more shopping for ready-made thrills, as if we don’t all need a break from stereotyped consumption.

The tone was set at the start of every episode, a bushy-tailed adventurer bragging his credentials – he’d been abroad (whoo!), he’d explored (double-whoo!), but now here he was slumming it on a mere path in boring old England, trying to work out why some fools in tweeds fifty years ago thought that walking 270 miles might be fun. His conclusion – it wasn’t enough fun. It was necessary instead to go rock climbing and white water kayaking. This made me cross.

The only bit I liked was when they showed an endearing soul who peacefully, harmlessly and all by himself walks The Way every year. An ordinary-looking chap with ordinary-looking gear, trudging along through what looked like Ribblesdale. The inevitable question: ‘So, why do you walk the Pennine Way every year?’

I jumped up from the sofa. ‘Mate!’, I cried, ‘No! Don’t justify! Don’t rationalise! Just shrug aimlessly! Say you do it just because of nothing, so there!’

I reckon he’d had his arm twisted by some vivacious production assistant, who from my own experience of TV work probably wasted three days of his life for thirty seconds’ screen time. He mumbled about his ‘fitness regime’. ‘I walk it every spring, then I’m fit for the rest of the year’. Not being unkind, he didn’t look like a fitness fanatic to me. Underwhelmed, the presenter bounded off to the car that would drive him to his next off-the-peg ‘adventure’.

I resolved immediately, then and there, that I would walk the Pennine Way again soon, simply, quietly and for no reason whatsoever. I looked online at cheap train tickets. Darn it, there was one available, very cheap. I bought it. And so, ladies, gentlemen and sheep, we present the Purposeless Pennine Way. OK, mostly sheep.

Day One – Edale to Kinder Low.

I leapt enthusiastically off the train at Edale. Well, alright, not exactly leapt. It was a quarter to three and so I started the way I meant to go on, with a nice cup of tea and a sit down in the excellent Coopers Café which, as you might hope given the location, is walker-friendly, filling your water bottle and selling takeaway cakes and sandwiches. You can camp here too, and they do breakfast.

Coopers Café, very nice too.

The sky was clear and sunny as I bounded up Jacob’s Ladder. Well, alright, not exactly bounded, but I was certainly buoyed upwards by excitement and glad anticipation.I also felt a remarkable sense of liberation and independence, not least I think because I was carrying no map and no guide book – I knew the way. Famous last words – a good job it was clear and sunny1. All the familiar landmarks of the Kinder massif were laid out before me, like balls on a giant pool table. It was wonderful.

The Pennine Way cairn on Kinder Low.

There was a chilly breeze on the top so I pitched my flysheet in tarp mode and in a dip that would normally have been a sopping quagmire but after this year’s remarkable drought was only slightly damp. I have never, ever seen these moors so dry, it was astonishing. If Wainwright had walked the Pennine Way in these exceptional conditions he’d have loved it a little more, perhaps.

Bone dry peat – unheard of!

Kinder Low wild camp. Sleeping up there is not officially encouraged so it’s especially vital to be discrete and leave absolutely no trace.

I had the entire summit to myself. The usual noisy aeroplanes glittered overhead in the low sun, the wind grew much colder; I had wear all my layers which was a bit of a worry on only the first evening. As I was finishing my sandwich and date slice (from Coopers) in the shelter of the tent, an unearthly sound suddenly drifted down to me, a kind of wailing and chanting; I’d never heard the like. I poked my head up out of my damp dip, it was coming from a group of people gathered around (and even upon) the triangulation point.

Kashmiri Muslims from Sheffield, they were singing praise songs to the Prophet on the summit, apparently this is quite the thing to do in Kashmir, albeit rather higher up. I went over to investigate, they were very friendly and invited me to join in. The kids wanted to tell me about their climbs of Ben Nevis and Snowdon; Dad preferred them to carry on chanting, the purpose of their ascents. It was God’s purpose that I should meet them up there, I was firmly informed. I apologised for my lack of Arabic and listened, intrigued, slightly embarrassed at my own lack of purpose but at the same time defiantly rather proud of it.

Sunset from Kinder Low – not a classic but good enough.

I did have an incidental agenda on this hike, if not an overriding purpose. Directly on the Pennine Way there are seven summits over two thousand feet. Kinder Low (2078), Bleaklow (2077), Fountains Fell (2192), Pen-y-Ghent (2277), Great Shunner Fell (2349), Cross Fell (2930) and Windy Gyle (2031). On three of these magnificent seven summits I had not yet camped out; Kinder Low was the first of those modestly extreme sleeps to purposefully be ticked off on this walk.

Knock, Great and Little Dun Fells are also over 2000′ but in my book they’re part of Cross Fell. Sleep on Great Dun and you’ll be irradiated by the radar station. I consider Cairn Hill and Auchope Cairn outliers of the actual Cheviot (2676), which is optional and who wants to sleep in a flat peat bog completely exposed to Scottish gales? Unless you’re actually in Scotland, of course, where that kind of fun is compulsory.

Day Two – Kinder Low to a plastic bag in some random midge-infested bog on Marsden Moor.

Yes, I still knew how to have fun, not least by getting out of bed at four am, after a rather parky night. Wandering around Kinder Low by moonlight, all alone, was also fun although perhaps not the kind of fun to tell the safety officer about.

Kinder Low triangulation point, four in the morning.

The sun rose as I ambled along to Kinder Downfall, one of my favourite places in the world for breakfast.

Breakfast at Kinder Downfall

To be honest, the downfall was more like the dryfall.

There was nobody about, and very little traffic on the A57 although what little there was I could clearly hear from Mill Hill through the still morning air.

Posing weirdly at Mill Hill cairn

Nobody on Bleaklow either, bar a solitary mountain rescuer running a few tens of miles to keep fit and a chap posing weirdly on the distant skyline. Don’t ask me, some kind of Tai Chi perhaps.

Unusually, all alone on Bleaklow

Pretty funky sky…

On Peaknaze Moor they were shooting and as I mistakenly took the peaty track away from Clough Edge, rather than the rocky track along the edge (a bad mistake in normal conditions but not too disastrous when it was all so dry), I nearly got mixed up in their bangy old business.

Tiny vintage waymarker on the trail above John Track Well, probably from 1965!

The whole experience was already so different in both character and detail from my last visit to Bleaklow that at John Track Well I suddenly felt a sense of purpose. The rivers were so low I could paddle; last time I’d nearly drowned leaping desperately across a foaming maelstrom. On this my fourth visit, the Pennine Way was already a changed place, showing me new things, exciting novel feelings.

Just uphill from the river I found a tiny vintage waymarker, crudely inscribed into a rock, partially hidden; I had to remove soil and moss to see it. This was the fourth time I’d walked past it but only now had I seen it, even though it had probably been there for fifty years. At the reservoir, brand new signs made finding the way down to the dam easier, not that I needed help now on my fourth attempt.

Perhaps my purpose was finally to walk The Way with the time and headspace to see change, rather than in a quotidian struggle merely to navigate the present. Walking the history, the heritage and the ongoing renewal of this remarkable trail rather than simply its distance, its obstacles. Not only looking, for the route, for the campsite, for the pub, but actually seeing.

Then I remembered I wasn’t supposed to have a purpose.

Well, exactly…

New signs, new directions, instructions, constant change.

Never thought I’d see Crowden Reservoir this low

Above Laddow Rocks I met a woman intrigued by my footwear. I can never understand why so many people think walking in the hills requires such different footwear from running in them. Dog walkers on Black Hill gave me the bad news that the snack van on the A635 had been absent for a while. Progress was so fast in the dry, sunny conditions I was up there by early afternoon; I’d thought about camping on the summit but was out of water, I stupidly forgot to top my bottle up from Crowden Great Brook and there’s nothing on the top of Black Hill but foetid swamps.

On Black Hill with my own personal wildlife guide. Not really, he was busy enumerating radio masts.

‘I see the trig point has sagged a bit more’ I said to the chap with binoculars. Surprisingly for a mast aficionado, he hadn’t noticed it wasn’t straight.

For this reason alone, I would have needed to continue but it was so pleasant and I had so much surplus energy I actually jogged most of the way down to Dean Clough. Where a dead sheep had recently been dragged from the stream. Oh well, at least it wasn’t still actually in the water.

Oh dear, I’m out of water. Still, so is the dead sheep.

At Wessenden Head a beautiful Short-eared Owl was quartering the rough meadows, I pointed it out to a young couple heading down to the reservoir and they kindly took an interest, the lad asking me ‘what does it eat?’ ‘Mostly voles’ I replied. Pause. ‘What’s voles?’ By the time I got down to the lodge I was tired and really wanted to camp somewhere, but the lower I descended the more midges appeared. I was so thirsty I eventually stopped at the bridge to brew some soup from river water. Clouds of midges latched onto me, they rapidly became maddening. I couldn’t bear to discard my irreplaceable soup, but it was still too hot to drink.

Throwing everything but the actual soup back in my pack, I slithered up one of the steepest little climbs on the entire Pennine Way with my two poles in my left hand and in my right hand a slopping titanium mug of Ainsley Harriott wild mushroom soup. The midges followed me, lured no doubt by Ainsley’s authentic mycological pheromones. Only at the Blakeley Clough tank was I left in sufficient peace to salvage the lukewarm dregs of Harriott’s fungal finest.

Finally enjoying my soup at the mysterious tank.

By now I was so tired I could have just flung myself into a swamp like Ophelia, my rucksack ‘pulling me from my melodious lay to muddy death’ (© W. Shakespeare). The moor was far too tussocky for the tent so I was forced to break out the bivy bag, brought with me for one of my three summit sleep-outs.

No photos exist of this camp, it was too awful. I lay in a random bog, midges descended once more but I had a piece of silk to cover my face; I fell asleep before sundown. In the morning I discovered that had I walked for another twenty minutes, I could have camped properly. At a pub.

Some will tell you the purpose of walking a trail is to have fun, or at least engender future fun after the event and perhaps also in others, through recollection. I expect we all know the three types of outdoor fun. Type One Fun is actually fun, and fun to remember. Type Two Fun is horrible at the time, but then becomes fun to remember. Type Three Fun is just horrible, and for ever.

Sometimes I fear I’m seeking out Type Two Fun for the sake of a tale to tell. Is my life really so dull that I must purposefully make it less enjoyable in order to make it more interesting? Then again, isn’t this the inevitable resort of any autobiographical writer? Ultimately, can Type One Fun ever be truly memorable? In which case, why do we allow ourselves to be constantly seduced into shopping for it?

Proust was big on this stuff. According to Alain de Botton he suggested “we become properly inquisitive only when distressed. We suffer, therefore we think”2. Wisdom acquired painfully through one’s own life is, according to Proust, far superior to that acquired painlessly from a teacher, including perhaps a professional Outdoor Activities Instructor with helmet, harness and risk assessment. Was acquiring a healthy dose of thought-provoking and memorable pain, solitary, unprofessional and free of charge, actually my Pennine Way purpose?

Day Three – Marsden Moor to May’s Shop.

It was no hardship to rise before the sun on Marsden Moor, because my appalling bivy bag was sopping wet inside with condensation. There must be something wrong with that thing, unless I’m just using it inside-out.

Sunrise over Marsden Moor

I squelched out of my plastic pouch like an unpleasantly mature pickle and ambled damply around the reservoirs in the dawn light. Their clear water was infinitely preferable for morning coffee to the Dean Clough sheep juice, which I happily discarded.

Would you believe that building is a pub at which I could have camped?

At Millstone Edge I thought someone had very kindly left a sack of muesli for passing hikers…

Drat, not muesli…

Blackstone Edge is one of my favourite Pennine Way locations; not only a lovely spot in itself, it means one has passed over and left behind the horrid M62. It also means the White House pub is near.

The horrid M62

Blackstone Edge in warm sunshine

The first time I’ve had any spare energy to inspect the Aiggin Stone – another example of walking the PW with a different kind of purpose

Ditto the Roman Road which is actually rather interesting

Both the Edge and the pub are also in Lancashire, hence it was necessary for me to wait an hour outside for the latter to open at midday so I could have black pudding for lunch in my ancestral county. Outside I met a fit looking man who said ‘I’ve always wanted to walk the Pennine Way but my wife won’t let me. She says I’m too old’.

‘Outrageous’, I replied, ‘how old are you?’ I thought he was about my age. ‘Seventy-eight’. ‘Ah. She may have a point. You could do it in sections…’ He seemed pleased with this idea and continued with the ten miles he was walking to Todmorden. Before lunch.

The pub was great as ever but I had to crack on as I knew with the steep climbs up from the Calder it would be a haul to get to May’s before she closed.

Looking back to the White House

Vintage reservoir architecture

On the way to Stoodley Pike I came upon a strange leather harness and some chains, lying on a rock by the trail. It looked like a waymarker for an S&M hiking club, or perhaps a bit of bondage-themed geocaching.

Cyril’s Seat, yet another favourite spot

At the pike a man with several misbehaving dogs enquired whether I’d seen their leads anywhere. ‘Ah…’

That Stoodley monstrosity

In Callis Wood I was nearly run over my a mountain biker descending at insane speed. By the canal, the alternative types who live there in vans and boats were already sipping wine and smoking whatever they smoke on garden chairs in the warm sunshine. I do sometimes wonder how and indeed for what purpose I’ve organised my own life so incompetently.

The Calder valley and its northern slopes have been completely taken over by Himalayan Balsam, it’s in every garden and all along the trail up the hill; I believe I may have predicted this in a blog two years ago #toldyouso.

The lovely ancient bridge at Hebble Hole had collapsed, and would you believe that according to a notice taped onto it the council has to apply, to itself, for listed building consent to repair it? A temporary scaffolding bridge was thankfully in place.The steps up from Colden Water had been very nicely repaired by the same council. It was a relief to reach May’s as I’d had a poor night. Her son asked if I had any washing to go in the machine, her daughter made me a mug of tea and sold me supper. It was like coming home, apart from the small sum of money changing hands and even that was painless as now – ta daaa – amazing news – May takes cards! Hence I spent a significant sum on essential stocks, for the purposeless privations lying ahead.

In the morning May gave me a free cake, for having already walked the Way three times, and we chatted about the BBC programmes. ‘That chap never walked the Pennine Way’, she laughed, ‘he just drove up here in a car. I said to him “you look exhausted” ’. She too isn’t walking very far these days, but she seems determined to keep running her small but miraculous retail empire, and purposefully to boot.

I should have asked her what the purpose of her shop is. Successful businesses surely always have objectives and mission statements, although I’m not completely convinced the latter have reached High Gate Farm Shop. It’s hard to imagine how something could purposelessly become so perfect, other than by evolving via natural selection over eons of course. Perhaps May’s is a kind of retail living fossil, slowly permineralising under its stone roof slabs, like an Archaeshopteryx. It’ll certainly be a missing link for the Pennine Way if May retires.

PENNINE WAY BLOG 3 – DAYS 4 – 6

Back to more typical Pennine Way conditions!

I’ve no idea why I decided once more to walk the Pennine Way. Reaction to the announcement was muted: ‘I hope you’re not going to start obsessing about rucksacks again’. Factually harsh – of all the men you’ll meet on a trail I am the least obsessive about gear; my rucksack was a lucky second-hand find on eBay. But fair in spirit, I suppose, from someone heading out into the rain to dig potatoes, by herself.

I was going to call this account The Pointless Pennine Way, but that seemed, although factually fair, harsh in spirit. ‘Point’ is more negative. “What’s the point of all this?” implies that there’s no point, whereas “what’s the purpose of all this?” very much implies that there is a purpose, though possibly hidden.

I had triggers: the TV programme and the cheap train. I had tactical targets: the three summits on which I’d not slept. I had a hankering for hills: living among the subtle topography of Norfolk I miss elevation. I had timing: I first walked the Pennine Way in 1999 a few weeks before I turned forty, I liked the temporal elegance of repeating it just before I turn sixty. We’ll see whether I again repeat it just before I turn eighty!

Cross Fell, April 1999. Photo by Ronald Turnbull.

Otherwise, I was determined not any impose expectations on this modest exploit. It would be just for fun, and whichever type of fun came along. The facts of the trail might be harsh – I’ve never yet walked the Pennine Way without almost blubbing at some point – but my spirit would be set fair and fancy-free. Clearly it would have outcomes on multiple levels but I felt that to identify and anticipate these in advance might constrain their potential. A useful excuse as I’m temperamentally averse to planning of any kind.

I decided to blunder up The Pennine Way as blindly as might be consistent with actual survival, making no itinerary and booking absolutely nothing, expecting only sore feet and sheep. As it turned out my feet were fine, so even that expectation was confounded. There were sheep.

World-class breakfast at May’s Shop

Day Four – May’s Shop to Pinhaw Beacon

They’d put the flags out for me on Clough Head Hill and as I was already feeling celebratory after a world-class breakfast of tea and sticky ginger parkin at May’s I tried to interpret them benignly as a gift. I graciously accepted their high-vis plastic intrusion into what’s otherwise, after a long interlude of farmland, a welcome return to some enjoyably bleak moors.

Strange plastic flags all along the trail, goodness knows why.

I was further cheered by recalling how in April 1999 I’d trudged through bitterly cold slush up here, my feet freezing in my leaky boots. That really was grim old-school fellwalking, this now was a dry, sunny morning stroll. The only fly in the ointment was that it was far too early for the Packhorse Inn to be open.

The Walshaw Dean reservoirs were extraordinarily low. ‘I’ve Seen ’em lower’, said a dog walker, ‘and this is when they drag out the stolen cars. And the bodies.’ It was very peaceful and with the rhythm of the easy walking I fell into a world of my own. I jumped out of my skin when a runner suddenly came charging down Lower Fold Hill. He then bagged a comedy double- double-take when on turning around and running back up, he hilariously made me jump again.

Ugly signage has returned to Top Withins, let’s hope it falls apart soon. At least it’s informative this time, not just ‘health and safety’.

Even Top Withins had only a handful of visitors, although I could see from the path ahead that there’d be at least a dozen people there by ten o’clock.

The very useful bad weather shelter at Top Withins was once more accessible.

…although it’s a bit draughty. One of those signs would fit this hole perfectly…

The lovely house at Upper Heights was for sale; if only I’d had £650,000, I could have bought it and re-opened the former much-loved campsite.

The vistas were broad, the air was still, the temperature benign; nothing happened to me at all, other than on the way up Old Bess Hill I picked up a revoltingly perfumed sweatshirt which I waved like a knight’s banner on my pole at a group of teenagers ahead. They all denied it belonged to them, although I suspect one of their number was secretly embarrassed at a terrible fragrance selection error in a cheap chemist. It’s probably still up there now, making sheep sneeze.

Old-school waymarking, with the new minimal marker post on the skyline (right).

The trend for minimalism and decluttering has reached Ickornshaw Moor where the motley cluster of sticks that used to decorate the rather subtle ‘summit’ has been simplified down to a single, slim pole. I should think this is much less visible in fog.

The newly-minimalised summit marker on Ickornshaw Moor

I was delighted for the first time ever to find one of the huts open and a denizen in residence; he told me all about them. The inherited rights exercised by the ‘freeholders’ who own these huts include rough Grouse shooting but by common agreement no birds had been taken this year as their productivity in the dry summer had been so poor.

Later in the pub I was told that no Ickornshaw Grouse are eaten locally as they’re much too valuable. For the price of one sustainable free-range wild Grouse harvested within sight of your house you can buy several bags of imported, frozen battery chicken, all the chips and a six-pack or three to wash it down.

At Low Stubbing I met more shooters in camouflage, carrying in lieu of a Grouse the largest wild mushroom I’d ever seen, “great for breakfast”. They confirmed a disturbing rumour my trail antennae had already picked up, that there was no food at the refurbished Hare and Hounds. On arrival I tried really hard not to argue with the new landlord about this. He was very friendly, his ale was excellent and more to the point I was dependent on him for the crisps and ‘spicy bar bits’ that were the only nutrition on sale.

It was baffling to me as a former owner of a rural hospitality business to see that they’d spent a fortune revamping the cosmetic appearance of the place to no visible commercial benefit while sabotaging a previously functional kitchen that could have been printing them money. When I acquired a run-down café on a country walking trail I sold chunky hand-cut sandwiches from day one even though the lights hung off the wall and the roof leaked, they were easy to make and I had bills to pay. The pub has since started doing food again, it sounds great and I wish them all success.

Camped on Pinhaw Beacon above the duck pools. These were noisily infested with foolish ducks that clearly hadn’t twigged their sinister purpose.

Distressed at Lothersdale’s formerly famous suet puds having been condemned to the dustbin of hospitality evolution, I trudged up Pinhaw Beacon in unusually low spirits. These were lifted by my discovery of an excellent camping nook near the summit, overlooking the duck pools.

I failed to realise that sleeping here would involve quacking ducks, both at dusk and before dawn. Lots of quacking ducks. Also midges – it was time to retreat into my allegedly midge-proof tent, albeit with confidence as it was sold to me as such by a Scotsman. If there’s a people on this planet that should know about midge-proofing it’s that noble race of mossie-fodder.

The lack of food at the pub meant I had to resort to Supernoodles, enhanced by more of Ainsley’s mushroom gloop and an extra packet of crisps that, due to unfamiliarity with his expensive computerised ’till’ (sorry, electronic point of sale system) the new landlord had been forced to give me as change.

Camp food at its finest.

Day Five – Pinhaw Beacon to Malham

Dawn from Pinhaw Beacon

I awoke feeling uncharacteristically gloomy. I was lonely and cold and could not for the life of me work out why I’d chosen to do this walk again when I could be at home with my loved one. I was pushing sixty and getting stiff in the mornings, my silly old eyes could hardly see in the poor light of a wild camping dawn. All in all, was long distance walking still really, sensibly, my thing?

A bit teasy on the Beacon.

Also dampening my spirits was the imminent walk through Cravendale, where the dairy farming is historically intensive and the ecology is commensurately tragic.

Intensively fertilised rye grass, shaved almost to bare soil at least twice a year. Where’s a Lapwing or Curlew to even hide, let alone nest, in this?

The haylage, which is seedless so unlike a traditional hay meadow provides zero bird food, is left after cutting to dry a little. It’s then raked up and baled in plastic by huge and terrifying machines. Yes, the system depends on plastic.

There’s nothing like a slap-up breakfast in The Dalesman at Gargrave to cheer me up, so I duly had one, even though I had to wait forty minutes for it to open at ten on a Sunday morning.

A sweet little old lady at the next table was visiting her son’s farm. Chatting, she told me she herself had recently starting growing ‘a few of those little carrots’. Envisioning her pottering around a cottage garden, Yorkie at her heels, I said “oh yes, farmers grow those in Norfolk”. “I grow some of mine down there”, she said, amiably, “this year in Norfolk I rented about six thousand acres”. I watched her totter across the road and lower herself with some difficulty into a racy Mercedes coupé.

The old PW sign outside The Dalesman

The walk from Gargrave to Malham is a doddle and along the river it’s even rather a treat in fine weather.

Pretty Airedale.

Aire Head, where the river springs mysteriously from the ground.

If you photographed all the vintage signs on the Pennine Way it would take you a year to walk it.

Approaching Malham

It was a fine Sunday afternoon so Malham was absolutely jam-packed, rammed and chock-a-block with people, the vast array of cars on the parking field gleaming in the sunshine for miles. After a restorative tea and curd cake at The Old Barn I walked through wave after wave of tourists returning from the cove to the campsite where, sentimentally, I pitched my tent in exactly the same place my partner and I had camped two years ago. Making exactly the same mistake of pitching by a damp, midgy river that I swore two years ago I wouldn’t make next time. There are drier, airier pitches at the top of the site.

The Lister Arms was so busy I tried the Buck Arms instead and ended up preferring it, less pretentious, less claustrophobic. I ordered a trio of sausages, imagining for some reason they would be wheeled in playing small musical instruments. All three were exceptionally delicious. The campsite was quiet, the shower was hot, my socks dried somewhat in the breeze. I felt a little happier.

I’m concerned at how a blog imposes purpose on every trail I walk. This time I very much wanted the trail to wag the blog, not the blog wag the trail. I was almost tempted to let the entire exploit sink unreported into the river of time, discarding my Facebook ‘virtual postcards’ to family and friends as if they were a sand mandala. What kind of boring, purposeless fool blogs about the same trail three times?

Munching my triyumyumyumvirate of sausages in the Buck Arms, I realised that this third-time-lucky repetition could perhaps serve my purpose as a ‘proper writer’. I’ve dutifully produced two practical Pennine Way blogs. Now, back on the same trail but with that job done, I was liberated from having to take accurate notes and free to think whatever crazy thoughts I chose. Also to invent crazy words.

How this might enable my trail writing to evolve I wasn’t sure, but at least this time my lame, clunky flights of fancy could crash and burn into the peat. I didn’t need to pick them out and polish them, because I might not even bother to write them down. Perhaps jettisoning the lifebelt of purpose would leave me floundering along the trail on a sinking ship of interesting whimsical introspection. A trail without a purpose is like a sausage trio con brio, like an armless buck, that kind of thing. Writing proper’s great.

Day Six – Malham to Horton in Ribblesdale

This day started nicely, I’d slept well, the weather was dry. At the top of the cove, though, there was a very noisy group of people, locked in endless complicated loud discussions that had nothing to do with their present location, and at seven in the morning. Ah well, at least I had a squashed sandwich from Gargrave Co-Op for breakfast.

Squashed sandwich brekkie above Malham Cove. Still dry at this point!

The incredible mammoth molars of the limestone pavement

I thought all the famous flowers at Malham Tarn would be long over but I’d failed to anticipate a gorgeous display of Grass of Parnassus.

Grass of Parnassus Parnassia palustris

It was clouding over, and as I rounded the back of the Field Centre it started to rain.

Clouding over, oo-er…

I was walking in t-shirt and shorts. As I ascended Fountains Fell I chose to simply pull my waterproofs on over these as the rain became steady. This was a mistake. By the top cairn, things were quite unpleasant.

I was dismayed. The plan had been to camp out on Pen-y-ghent, the next of my two unslept summits. I’d imagined a pleasant afternoon fossicking around up there, a little light exploring, a leisurely Supernoodle supper. Now I’d be up there by two in the afternoon and the rain was teeming down with no sign of stopping. What on earth would I do up there for sixteen hours in pouring rain?

penyghent-view-pennine-way-yorkshire

Views of Pen-y-ghent were not extensive…

No photos exist of this ascent of Pen-y-ghent. The rain hammered down, my phone would have been ruined in seconds. I clambered up the steep bit, which resembled a vertical stream, following a northern lad of asian heritage wearing football shorts and the kind of black anorak you see on market stalls, unzipped. “I think I might buy some waterproofs”, he said on the top, still with his hood down, “I quite like this hillwalking”. His enviably dark and thick hair was stiffened with one of those products young people spend fortunes on; each spikelet was crowned with a globule of water, he looked as if his head was covered in those little silver balls we used to put on fairy cakes as children.

A completely soaked couple of my own age (“we’ve got to that point when your waterproofs are useless but you’re past caring”) imparted terrible news. The Pen-y-Ghent Café seemed to be closed! No! Impossible! What about my pint of tea and my buttered Chorley cake? Ridiculous.

Perhaps with the shock of this news I suddenly felt very cold. I jogged down quite a lot of the big new stone steps and the interminable drove road. Even with this effort I failed to warm through. I realised, too late, I should have stopped and put on proper trousers and a warm top way back at Malham Tarn. Not only was I soaking wet, I’d acquired some bad chafing from the overtrousers rubbing my bare legs while jogging, a schoolboy error.

At Horton the café was indeed closed, I could hardly believe it. I made for the campsite which was itself in a slight crisis as Chris the proprietor had been hospitalised with heart trouble. I pitched the tent on soaking wet grass and lingered gratefully under a hot shower. Luckily the Golden Lion opens at three, so having warmed my muscles I could retreat there to warm my cockles. The young manager once camped wild on the west coast of Scotland for two months, he told me, living off the land. He had to call it off, he said, looking meaningfully at me, because his companion got hypothermia.

The food in here was charmingly old school, including a steak and ale pie that was actually a bowl of (very good) stew with a spurious free-floating puff pastry hat perched on top. I prefer a more formally constructed pie myself but I wasn’t about to moan, it was delicious.

penyghent-cafe-closure-sign

Pen-y-Ghent Café disaster!

A remarkable thing happened in the Golden Lion; an Irishman, who with impressive dedication to fashion was hiking with dungarees in his pack as evening wear, bought me a beer. This has never happened before, not on the Pennine Way I mean, obviously it’s often happened in Ireland. I feel bad about this because not only did I slope off to bed without buying him one back (I did warn him this was likely) but I’d criminally misled him on the price of the pub’s cosy bunkhouse, which he’d asked me about after also descending soaked and frozen from Pen-y-ghent.

I’d told him from memory it was twenty-something pounds, on hearing which he decided to camp, damply. Imagine my shame (and annoyance after also pitching a tent to economise) on finding it was only twelve pounds. The twenty-something I’d remembered paying on my previous visit had been for two people! I didn’t quite get round to confessing this during our entertaining conversation. Apologies, dale buddy, and thanks, I enjoyed the beer and your company. Not necessarily in order of importance.

One thing I routinely was asked in pubs was “why the Pennine Way again? Surely you should be ticking off some other trail from the list?” Because I’m a trail walker, not a trail collector. Because I’ve done one new trail already this year, so I get the rest of the year off for good behaviour. Because I like the Pennines.

There’s a ridiculous superabundance of trails and I’m in my sixtieth year, I’ll never do them all. To try and choose another purely on grounds of neophilia seems both invidious and hazardous. On what criteria? Not everything in life has to be novel, any more than it has to be purposeful.

There’s also a ridiculous superabundance of outdoor blogs. I write mine for fun, because I like writing. It also gives me back the gift of a vaguely coherent souvenir of my own unimpressive adventures. I’ve never been able to keep up a journal on paper, but I find blogging congenial and the feedback is nice (thank you). To quote Wainwright: “I wrote a book of my travels, not for others to see but to transport my thoughts to that blissful interlude of freedom”.

The blogs I least enjoy are the most blatantly purposeful; weekly cut-and-pastes of the generic second-hand ‘advice’ that wastes the first twenty pages of every trail guide. I’ve observed an inverse correlation between their number of listings*, ‘top ten blog’ awards and endorsements and the novelty and quality of the ‘advice’. I’m also suspicious of outdoor blogs by young female ‘adventurers’ who adventure in impractically tiny shorts and coincidentally have about forty thousand followers. For some reason you never encounter these fairytale creatures when you’re splodging through a bog in gathering dusk and a relentless hoolie and you could do with a bit of glamour to cheer you up.

Sitting in the Golden Lion contemplating the ontology of stew in a hat, I realised my suspicion of the overtly purposeful goes for trail walking as well as blogging. I was starting to understand how the motivations and rewards for both may be harder than I thought to disentangle. I was pleased to have emphasised my purposelessness to myself by abandoning one of my summit camping objectives, although obviously that TV presenter would have still camped on Pen-y-ghent in the rain. Obviously.

PENNINE WAY BLOG 3 – DAYS 7 TO 8

The Purposeless Pennine Way, in which while blithely enjoying my favourite hike in perfect weather, I meditate upon feeling weird, failing, annoying other people and disliking a book.

Something of a Philosophical Pennine Way. Practical Pennine Ways are also available, both south to north and north to south.

pennine way in yorkshire england hiking national trail

A trail gnome that seemed to have lost his fishing rod, at Ling Gill Bridge

We must be purposelessnessless, as Rowan Atkinson said in a comic monologue that seems highly relevant to the Pennine Way 1. To achieve a purpose is virtuous ‘work’, requiring ‘effort’. An absence of purpose on the other hand is a hallmark of vacuous laziness.

Strangely, I found once I’d embarked on the Pennine Way purposelessly, with neither objectives nor a plan, mentally I was working harder. I had very little idea from day to day what I was doing, let alone why. Each day I had to work it out, to reinvent it, as atheism imposes the intellectual effort of devising your own morality.

Rather than easing my mental Mercedes on cruise control along a mental motorway, I was a learner on a wobbly mental moped in a dark and narrow country lane. Was I proud of my lack of purpose, or embarrassed by it? Did I feel settled, at home, at peace with The Way and with myself or was I now even more of a guilty loner, a shifty outsider, a weirdo, for repeating the same trail?

yorkshire dales pennine way dismal hill

The two nearest hummocks in this picture are (seriously) called Rough Hill and Dismal Hill; just past them my mental moped got lost and had to retrace its wobble.

Was I happily and lazily liberated by my independence from maps, guides and itineraries, or more busily and anxiously concerned about my consequent dependence on the fortuitous reappearance of vaguely remembered landmarks, not to mention random food and shelter?

Walking entirely without a plan, it was necessary to give actual thought to where I might end up sleeping and eating. The Pennine Way isn’t an entirely trivial exploit; as I’d learned yet again on descending from Pen-y-ghent it’s quite possible while walking it to become tired, cold and wet.

Did I even want to walk the entire Pennine Way again? Protestant Work Ethic me wanted to chalk up another success. Liberated, alternative me wanted to fail, to digress, to snap my fingers at the impertinent tyranny of an official trail. Part of me wanted perversely to subvert my objectives.

I hope you’re not expecting answers to any of these questions. I always say that if walking the Pennine Way answers your questions, they must have been pretty daft questions.

Day Seven – Horton to Hawes

I was woken by some very loud Irish snoring from an adjacent tent; that will teach me to remember bunkhouse prices correctly. I was happy about this, though, as I didn’t want to miss my traditional Wensleydale sandwich at the Hawes Creamery so I needed to get going.

Everything was very wet and everywhere was very quiet, in fact I didn’t meet another human being for several hours, not until the Cam High Road where a young, long-haired lad was walking the Dales Way in the guise of a tinker with billy, socks, shirt and all manner of other gear hanging from the outside his pack to dry.

pennine way national walking trail yorkshire england

After a while, a splash of sunshine painted Ribblesdale with a brighter palette.

There were a few more wild flowers along this section; quite a bit of Sneezewort by the trail and then behind the sheep-proof fence at Ling Gill nature reserve in a hint of what the moors might have looked like before over-grazing, masses of Devil’s-bit Scabious with lots of Red Admirals feeding from it.

sneezewort on the pennine way

Sneezewort Achillea ptarmica

ling gill natinal nature reserve yorkshire

Ling Gill itself is hidden below the trail but the flowers and butterflies along its top edge were pretty, with lots of Devil’s-bit Scabious Succisa pratensis

On Birkwith Moor I carelessly managed to get lost, carrying straight on over Low Birkwith Moor towards the forestry instead of turning left immediately after the gate (point C on the National Trail Guide map, page 89). I was quite pleased though that I’d realised my error fairly quickly, from increasingly becoming aware that I didn’t remember these surroundings. I retraced my steps and a sneaky peep at the GPS told me I’d gone astray near the appropriately-named Dismal Hill.

pennine-way-dismal-hill-screenshot

Seriously, Rough Hill and Dismal Hill. Note the GPS arrow pointing in an embarrassing direction as I retrace my steps. Mapping copyright the OpenStreetMap contributors, from OsmAnd

pennine way yorkshire dismal hill gate

Take the left fork uphill after this gate, rather than the alluring path straight on.

At Cam End I suddenly encountered the answer to something I’d wondered about for years – why this section of the trail is so wide and is maintained to such a high standard. It’s used by enormous forestry trucks – keep your eyes peeled!

yorkshire forestry truck in pennines

So that’s why the trail is so well-maintained hereabouts.

whernside from the pennine way yorkshire

Looking over to Whernside from the path to Old Ing

At Kidhow Gate I was depressed to witness the employment-creating ritualised cruelty of driven shooting. Large, shiny expensive vehicles whizzed up and down the ugly tarmac road that’s been dumped onto a formerly picturesque moor. I could smell the diesel fumes and hear the engines, as well as the shots, from a mile away. Then, looking back over Snaizeholme I was cheered to recall an observation my Irish chum had made in the pub.

In the West of Ireland, he said, there are little houses everywhere, hardly anywhere feels actually remote. He’d been amazed, he said, by how in England with our much greater overall population density we could somehow still have kept wild, remote landscapes, and right in the centre of the nation.

It’s been subsequently explained to me that this has to do with the relative timings of enclosure acts, famines, clearances and other historical catastrophes and that all these hills and moors would indeed at one time have supported small, visible homesteads. Gazing nowadays on the North Pennines moors that we value for their bleak emptiness it’s certainly something to ponder.

yorkshire moors pennine way

The bleak emptiness of this landscape is both wonderful and baffling.

In the Wensleydale Creamery, a cheese factory, where they make cheese, a plain cheese sandwich is no longer on the café menu. I had to negotiate with a very busy young lady of East European heritage to obtain one, fortunately with her good-humoured collaboration. Our mutual subversion of the official repertoire was aided by a samizdat list of ‘simple sandwiches for awkward old people’ that she kept hidden under the till. Mine was delicious.

hawes creamery wensleydale cheese sandwich yorkshire

The now traditional Wensleydale sandwich.

Just uphill from Hawes I’d met a young Belgian Wayfarer, southbound. On my asking what had been his favourite bit so far, he recalled his traverse of The Cheviot and every detail sounded suddenly, happily familiar to me. For a moment I felt as if, like Simon Armitage, I was ‘walking home’, albeit in the other direction.

Another impressive experience had been his breakfast at the Hawes Hostel, where with the Golden Lion’s WiFi I’d booked my first night indoors on this walk in consideration of their large drying room and the soaking wetness of all my kit. That was annoying, as I was planning to leave Hawes too early to sample it.

I did enjoy once more the fabulous Cod Special in The Chippy which was as utterly perfect in its hot, fresh simplicity as ever and, again, faultlessly and kindly served by a young East European woman. It baffles me what will happen to our hospitality industry post-Brexit. Perfect too was the Timothy Taylor’s Landlord in The Old Board Inn, where I gave up my table and sat at the bar so a couple could eat. They were from Norfolk. As was the next couple along – five of us flatlanders, meeting randomly, in a pub in Hawes. As our talk was of familiar places, in an odd way I felt I’d already walked home.

hawes wensleydale yorkshire

A perfect sunny evening at Hawes

Walking The Way as familiar territory, knowing the way (except at Dismal Hill), I often found myself wondering whether I was now truly at home, in my own back yard. Whether as a veteran, already a member of the Free Half at The Border Club, I was to a greater or lesser extent part of a community.

Whenever I encountered another Wayfarer, I couldn’t help wondering whether in their eyes my prior experience promoted me to Trail Sage, or demoted me to the awkward squad. Often I deliberately kept quiet about it. Normally when you meet other walkers on the Pennine Way there’s a certain camaraderie as you’re all in the same bog of despond. The last thing you need to see is someone who mysteriously isn’t lost, swanking along without even a compass round his neck.

As I got further north this problem receded. As at Dismal Hill, my memories became a little vague in places and I started making the odd comforting mistake, acquiring the odd comforting anecdote, handy scraps of self-deprecating conversational currency. To feel at one with a community of travellers, perhaps you need yourself to be feeling a bit lost, a bit deracinated. The times I felt most at home on The Way were also those when I most felt a stranger to my fellows.

vintage ice cream van at Hawes yorkshire england

Day Eight – Hawes to Tan Hill

This was a great day, great views from Great Shunner, a great lunch, a great pub, a great supper. Oh, and a nice walk too. It started badly though when the hostel warden threw a spectacular sulk because I asked him if he’d reconsider his having turned on a loud radio in the lounge where I was sitting peacefully, all alone and in contented silence, at 6.45 am.

hawes-yorkshire-wensleydale-early-morning

A peaceful morning stroll through quiet Hawes

wensleydale yorkshire pennine way

Morning light on the way out of Hawes

To be fair, I may have spoken rather intemperately. Switching a radio on without asking first would be considered the height of rudeness in our house and would probably instigate the rapid movement of heavy objects through the air, not to mention bad language. I tend to forget other people like the radio, something he pointed out with surprising vehemence. ‘But there’s only me in here’, I recklessly retorted, ‘and it’s not for long, I’m going soon’. ‘GOOD!’ he snapped.

Rather than acquiesce with professional grace he insisted on further prolonging this embarrassing argument in a manner too tedious to transcribe. Honestly, where does the YHA find these people? I sloped off up Great Shunner Fell in a bad mood, luckily with a legendary mince and mushy pea pie in my pack to cheer me up. Also sunshine.

wensleydale yorkshire dales england

The view of Hawes improved the further I got from the hostel, but I’m sure this was just coincidence.

wensleydale yorkshire

Cheesy clouds down below in Wensleydale

Yes, there was sunshine on Great Shunner Fell! And – ta daaa – extensive views!

pennine way yorkshire england fells moors

On the way up – the sky looks promising!

The air was still and warm, I was alone, it was very quiet. Shame I didn’t have a portable radio to liven things up.

pennine way yorkshire england

Approaching the summit shelter

It was actually a pleasure to mooch about on the summit; the last two times I’d been here conditions had been foul.

great-shunner-fell-view

Extensive views, as promised.

Cloud inversion in the Vale of Eden

The clouds rose and swirled about as I watched. On the skyline right of centre, Cross Fell. I could clearly see the radar station on Great Dun Fell.

Northbound, the route off Great Shunner is easy to find even in poor visibility.

Even in poorer conditions I quite like Great Shunner Fell. Route-finding is easy and the ascent although long is not particularly arduous in either direction. At the top you always somehow feel as if you’ve got somewhere meaningful, even if you can’t see a thing. The vegetation is surprisingly colourful and there’s supposed to be Black Grouse up there although they’re darned elusive. In weather like this, it’s one of the great highlights of the trail.

On the way down I started to meet people. The lovely Kearton Country Hotel at Thwaite was quite busy, but not too busy to serve me a nice lunch of a fish finger butty and classic fruit cake with Swaledale cheese, as well as their famous ginger biscuits with the coffee.

The classic view back to Thwaite

In places above Thwaite the trail has been seriously undermined by rabbits. I won’t be surprised if it starts washing away soon at this rate.

Parts of the trail along here are basically a rabbit warren

Walking into Keld is always quite exciting, it feels magical.

For some reason Keld always has a slightly magical feel, it’s definitely a bit of a cosmic omphalos, snuggled in its bosky dell, its energies stirred by pixy picture-book waterfalls. I always expect my photos of Keld will turn out to have unexpected fairies lurking in their corners. To get them on a phone rather than on film I’d probably have to download a supernatural app.

The cosmic omphalos of Keld

You’d be a pretty wet fairy if you stood where I’m standing in winter…

Smart new signage, much appreciated.

It takes longer than you think to get up the hill from Keld to the wonderfully-named Arkengarthdale, but the first view of the pub is another magical Pennine way highlight. Especially so if you can’t actually see it due to freezing fog or blizzard, but today was a day of continuing extensive views.

Classic first view of the Tan Hill Inn.

Tan Hill was under new ownership and I was concerned by reports they planned to professionalise the place. Thus far they’d got the balance right, investing judiciously but leaving much of the pub’s character unchanged. There was even a typical Tan Hill moment when a couple moving rooms found their possessions had been hidden away by the cleaner and nobody knew where. The barman ineffectually tried to find them, becoming a little flustered. After an hour of this pantomime his young lady colleague offered to take over the search. She opened one cupboard and immediately reached down the lost items. My partner would have had something to say.

It was a lovely evening, the beer was great and my dinner was fantastic. As I was feeling mildly heroic for getting this far, I met a man who’d walked the Pennine Way in 1966, soon after it had opened and through its notorious but now only legendary bogs. In jeans and dubbined leather boots, carrying a canvas tent. I felt mildly silly.

He was pleased, he said, that the trail is now easier and more enjoyable walking, as it enables people to see more of the landscape and in different ways. In those days the Pennine Way was indeed an arduous struggle. He’d enjoy walking it again a lot more now, he felt, were he physically able.

This reminds me that I didn’t really enjoy Simon Armitage’s Pennine Way book2 when I first read it. It was given to me when I was preparing to walk The Way in 2016 and I suppose I’d hoped to glean from it simplistic information specifically about the trail and about the process of walking it. It seemed an unsatisfactory and in itself dissatisfied sort of book.

As with the BBC programmes, just walking the Pennine Way wasn’t interesting enough. To sex up the story it was necessary to bolt on the spurious ‘purpose’ of walking ‘home’, and the conceit of purposefully paying his way as a ‘troubadour’. The book ends with a mean-minded calculation that he has made a loss on the enterprise, as if any of us don’t walk the Pennine Way in permanent and profound debt, to the trail pixies, to Tom Stephenson, to Bill Gore, to road builders, train drivers, parents, teachers and the NHS, to slaves, kings and songwriters. Possibly also poets. My entire lifetime earnings would nowhere nearly fund all the gates, waymarkers and flagstones that have been installed and reinstalled on The Way in its fifty years of existence.

Armitage gets lost multiple times, even though for much of The Way he is not alone but in jolly, diverting and often professional company. He can’t even get it together to finish the damn trail! He uses baggage transfer. What a shambles.

Re-reading the book now I’m seeing it with different eyes. Relieved by my own serial completions from needing to learn about the Pennine Way and its walking per se, I’m able to absorb his trenchant observations of people and places, the verve and sheer competence of the writing with its consistent wry energy. The poetry of it, his rueful but defiant ultimate position that finding your way home is more important than finishing any arbitrary trail. I’m now engaging with the book on a much broader front rather than seeking in it a narrow, specific purpose. Now I’m over the practicalities it’s more fun and it’s teaching me more things. Not that I’m re-reading it purposefully, of course.

1 Many thanks to Lonewalker for kindly reminding me of this monologue via Twitter.

2 Armitage, Simon (2012), Walking Home – Travels with a Troubadour on the Pennine Way. London: Faber & Faber. I’ve a soft spot for the boy Armitage as when I owned a nature reserve he kindly gave me permission to reproduce a poem from this book on my signage. Cheers!

PENNINE WAY BLOG 3 – DAYS 9 – 11

The Purposeless Pennine Way, in which while strolling along on what most people would call a holiday I meditate upon work.

Something of a Philosophical Pennine Way. Practical Pennine Ways are also available, both south to north and north to south.

Day Nine, Tan Hill to Holwick

wild camp pub pennine way dawn yorkshire

Early doors at Tan Hill, my gear half packed, the inner tent drying in sunshine on the rocks, anticipating an excellent breakfast. It’s always all good here.

The ‘campers’ breakfast’ at the Tan Hill Inn was perfect, and great value for a very reasonable seven pounds – I fear it’s gone up since. The only downside for me was the unsolicited ‘breakfast news’ on a large TV dominating the room. I’d learnt my lesson at Hawes and said nothing, particularly as this time I wasn’t alone. Also, to be fair, I was glad of the weather forecast.

A table of upmarket oldies were section-hiking the Pennine Way together in annual small chunks. They became positively animated in their discussion of what always seems to me such bogus ‘news’, in the manner of people who were all at Oxford together fifty years ago and have been running bits of the world ever since. My world, our world. The manner of people who rather than set out over Sleightholme Moor on foot would shortly settle into an Audi and whizz off to Whitehall or the UN. When their conversation did revert to the trail it was firmly objective-focused. Just to overhear them felt like a Monday morning.

pennine way pub tan hill yorkshire

By the time I’d enjoyed my lavish breakfast the sky was blue over Tan Hill.

In some ways I too was approaching the Pennine Way as a job of work despite my avowed purposelessness, and I’ll be glad never to have the job of typing that again. I did try hard to visualise both the trail and its walking as pieces of conceptual art, which of course they are, but at the same time it’s a tough old hike (harder than the Cape Wrath Trail in my opinion) and to attain its completely arbitrary endpoint does require a certain stubborn focus.

It’s a profoundly physical experience; exercise quite unlike weekend football or evening squash, a relentless day after day physicality that otherwise only those doing hard labour for a living can truly know. It’s appallingly tactile; for days on end you’re in close touch with the elements, intimate with water, mud, sweat and seemingly infinite quantities of sheep poo, intimate with your gear and with every stitch of your tiny repertoire of clothing. Between undoubtedly wondrous highlights there’s quite a lot of connecting tissue. You see ugly things, even dead things, though hopefully not including other hikers. Not dead, I mean, I can’t promise not ugly.

It’s voluntary work, of course, and on a zero-contract contract other than with yourself. And it’s shamefully easy compared to the daily existence of those who lived high in these hills, as many did, in years gone by, scraping precarious livings, labouring harder than I can even imagine and only marginally staving off hunger.

Tan Hill reminds us of this heritage with maps on the breakfast room wall of the old Arkengarthdale mine workings. At what’s now a leisure destination for bikers, hikers and Instagram likers, people lay daily in darkness, filth and freezing water grubbing coal with pickaxes from a scrappy seam, braving dodgy shafts, collapsible tunnels and the terror of firedamp. The Pennine Way was a workplace then, alright, and Tan Hill’s coaltown rats had every right not to like Mondays.

pennine way lookingback to tan hill

Final view of Tan Hill. From now on it gets wilder.

Even in the driest summer the words ‘dry stroll’ and ‘Sleightholme Moor’ can’t be used in the same sentence. It was a moderately boggy stroll, but still very easy. I got to the green bridge unbelievably quickly, shaking off into the warm sunshine my memories of stepping through sheets of April ice to go up to my knees in peaty slush. I won’t be walking the Pennine Way in April again anytime soon.

gods-bridge-pennine-way

God’s Bridge

There wasn’t another soul about, not one, and there were no birds either other than Grouse; all the noisy waders I’d seen at Sleightholme Beck on my previous June visit had gone, I hope just seasonally. All was quiet, until from a good mile away I began to hear the intrusive roar and rumble of the traffic on the A66.

pennine way halfway trail marker

The famous ‘halfway, suckers’ trail marker at the A 66.

Which one is never entirely displeased to hear as it means, amazingly, that the halfway point on The Way has been reached. For some reason, northbound the first half always seems to take forever, the second half no time at all. I’m getting fitter by then, I suppose, and also I dare say the novelty is wearing off.

pennine-way-ravock-castle

Fit but jaded – ?

pennine way deep dale shelter

From this cairn just past Ravock Castle you can see the useful bad weather shelter at Deep Dale (arrowed). It would be great if a few more landowners were that kind to hikers.

At Race Yate I paid a courtesy call to the spot among unpromising reeds where I’d camped in surprising comfort in October 2016, despite pitching my tent in virtual darkness having carelessly run out of post-equinoctial daylight. I was pleased now in pre-equinoctial daylight to see it had been, by my standards, an almost competent choice of campsite.

pennine-way-race-yate

Walking the Pennine Way will soon be taking me a month if I have to re-visit everywhere I’ve camped.

For many Wayfarers, including me, this is one of the nicest and most relaxing sections of the trail. It’s wild but unchallenging, quiet but unisolated; you walk through beautiful and varied landscapes, you see lovely views. It’s a good long leg-stretcher but you’re still essentially on a pleasant country walk from a pub to a pie shop.

Sadly there was no sign of any bunk barn availability at Clove Lodge, which leaves accommodation for non-campers on this section problematic. (Update 2020, I believe the wonderful bunk barn is open again).

grassholme reservoir county durham uk

Grassholme Reservoir, where there was still a Portaloo in the car park. Due to its generous size I’ve found this very useful not just for its advertised function but as a brief respite under cover to sort myself out in bad weather.

Tan Hill to Middleton is easily achievable if you’re still in good shape, but if you’re footsore and fed-up by this point it can feel a bit ambitious. Bowes is an option, of course, but I was too preoccupied to consider it. Apart from a friendly chat with the kind proprietor of the little trail tuck shop by Collin Hill, I was on a mission. A pie mission.

pennine way tuck shop near middleton teesdale

The friendly little tuck shop near Collin Hill, where you can also fill your water bottle.

McFarlane’s, the legendary butcher and piesmith at Middleton on Teesdale, closes at five and thanks to my extravagant breakfast at Tan Hill I was cutting it fine. For the sake of one of their stunningly good pork and apple pies I literally ran quite a lot of the way down into the town. Lose calories to gain calories, I figured, as I staggered into the shop sweating profusely at four forty-five.

kirkcarrion teesdale england uk

As ever, Kirkcarrion broods over Middleton

‘Ha ha, we’re open til seven’, they said cheerily. Luckily for my small remaining safe margin of blood pressure this was a joke. I bought arguably a slightly reckless number of pies. Also a tremendous corned beef and potato slice, to eat immediately. It was then necessary to buy further provisions in the Co-op; Dufton is always a bit of a movable feast, there might be food, there might not be, then there’s Cross Fell to consider, and then who knows what there might be to eat at Garrigill?

All in all, you do need to do the shops at Middleton although tragically the lovely old Post Office and sweetie emporium where I traditionally posted home my surplus gear has closed. Luckily by my fourth Pennine Way I’d just about eliminated surplus gear, other than one redundant pair of warm socks, a hangover from memories of April. This time I walked the entire trail in skinny mesh-top running socks (Higher State ‘Freedom’s) which proved durable and dried very quickly.

Wary of wild camping in popular Teesdale, I was aiming for Low Way Farm at Holwick where you can camp legitimately for just a fiver. The weather looked ominous but locals were still out walking dogs. Helpfully, several told me I still had quite a way to go.

The site was unsigned and virtually invisible from The Way, I only just spotted a camper van behind a wall. By now it was absolutely teeming down with rain. A man who from the smell coming from his enviably watertight palace on wheels was boiling an entire steer on his camp stove, or perhaps heating a Desperate Dan-sized Cow Pie in his camp microwave, told me to ‘pitch oop, summun’ll coom’.

I pitched oop, on grass so wet if I’d rolled around on it naked I’d have been rendered quite hygienic, albeit hypothermic. Rain hammered on the flysheet. Then it stopped quite suddenly, the sun came out and with the light-headed relief that accompanies such ineffable transitions on a trail, I ate a McFarlane’s pork and cranberry pie. It was awesome.

Yet another life lesson from the Pennine Way: wise man doesn’t beetle about virtuously putting tent up in shower of rain like idiot cross between Bear Grylls and Doctor Foster. Wise man calmly waits for better weather, eating pie in toilet.

pork and cranberry pie mcfarlanes middleton

McFarlane’s finest. Apart from their pork and apple.

No one came so conscientiously I walked up the track to the farmhouse to pay, it seemed a long way after hiking from Tan Hill. There was nobody home, but the café kitchen door was open and on the bench were a dozen freshly-baked Victoria sponges, their aroma was overwhelming. I could have eaten an entire cake and nobody would have been any the wiser. Not about who did it anyway; counting cakes is normally a core skill for café proprietors.

As I was about to poke a fiver through the letterbox there crunched around the corner on the pristine leather driving seat of an upscale Range Rover what would in my childhood have been known as ‘The Farmer’s Wife’, now of course more correctly as Joint CEO, Low Way Agricamping and Catering Solutions LLP.